Site Description

Open to read more

This section provides a description of the developed areas, Tribes, physical features, hydrology, climate and winds, and tides and currents found along the Middle Columbia River (MCR) corridor and includes an overview of the oil spill risks in the region.

The Columbia River travels 1,243 miles, originating in British Columbia, Canada and running through Washington, providing a border between Washington and Oregon before eventually entering the Pacific Ocean. Although the Columbia River originates in Canada, the NOAA river mile system used in these geographic response plans (GRPs) begins at the confluence of the river with the Pacific.

The Lower Columbia River Geographic Response Plan (LCR-GRP) starts at river mile one and ends at the base of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) Bonneville Lock and Dam located at river mile 145.4. The Middle Columbia Region begins at river mile 145.4 on the upstream side of the Bonneville Lock and Dam and is subdivided into four separate GRPs, each specific pool delineated by one of four USACE dams in the region: Bonneville, The Dalles, John Day, and McNary. There are four additional GRPs above the Ice Harbor Dam on the Snake River.

The MCRM-GRP encompasses the McNary Pool (aka Lake Wallula) and covers a 50.5-mile reach of the Columbia River, continuing to run east from just upstream of the McNary Lock and Dam (located near river mile 292.6) to the Ice Harbor Lock and Dam (located at river mile 9.7 on the Snake). Additionally, the plan covers four miles of the Yakima River along with a portion of the Hanford Reach. In Washington, the planning area resides within Water Resource Inventory Area Rock-Glade (WRIA 31), Walla Walla (WRIA 32), Lower Snake (WRIA 33), Esquatzel-Coulee (WRIA 36), Lower Yakima (WRIA 37), and Alkali-Squilchuck (WRIA 40). In Oregon, it includes portions of the Watermaster District 5 (headquartered in Pendleton).

Developed Areas

The cities of Pasco, Richland, and Kennewick (aka the Tri-Cities) are located within the boundaries of this planning area, as well as portions of Benton, Franklin, & Walla Walla Counties in Washington, and Umatilla County in Oregon.

Tribes of the McNary Pool

This planning area is within the usual and accustomed territories of several American Indian Tribes. There is no Indian reservation(s) located within this GRP. However, the nearest reservation of Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR) is located near the City of Pendleton, OR approximately 26 miles southeast of the Columbia River.

Other federally recognized Tribes with access to the resources of the McNary Pool may include the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde, Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, and the Nez Perce Tribe.

Tribes can fill many roles during an oil spill response including full participation in Unified Command, providing resource specialists in the Environmental Unit, monitoring on-scene operations, and more. Information regarding tribal participation in a response is available on the Northwest Area Committee/Region 10 Regional Response Team website. Contact information for the tribes in this planning area can be found in the Resources at Risk section and on the Spill Response Contact Sheet of this GRP.

Physical Features

Open to read more

Geology & Landscape

Volcanic activity built up a stratum of mud, ash, and lava in the geologic column in what is now eastern and central Washington and Oregon beginning some 55 million years ago. Basalt flows then covered the area in layers, forming a strong foundation of basaltic rock. Subsequent lava and ash eruptions raised the Cascade Mountains. As the mountains rose, the Columbia River carved out a deep gorge. The Missoula Floods battered the gorge over 100 times when the ice holding back a vast inland Lake was repeatedly breached, scouring the landscape all the way to the ocean. Another ancient lake, Lake Lewis, formed behind the Horse Heaven Hills, eventually carving an exit through what is now known as the Wallula Gap (NPS). Basalt cliffs make shoreline access difficult if not impossible in many areas along the Columbia River gorge.

Cultural Features

There are two National Register of Historic Places archaeological districts within the MRCM planning area (NPS):

- Tri-Cities: this district spans approximately 22 miles from the Hanford Reach to the part of the Columbia between the Cities of Pasco and Kennewick.

- Lower Snake River: this district runs from the Ice Harbor Dam at river mile 9.7 to the confluence with the Columbia River.

Shoreline Description

Despite the diverse change in scenery surrounding the Columbia River through each of its various pools, the shoreline habitats remain relatively consistent over the course of the Middle Columbia River. Along the Columbia River the following shoreline types are present: exposed rocky headlands, wave-cut platforms, pocket beaches along exposed rocky shores, sand beaches, sand and gravel beaches, sand and cobble beaches, sheltered rocky shores, and sheltered marshes (NOAA).

Dams & Irrigation

The MCRM-GRP includes the USACE’s McNary Dam (River Mile 292.6) and Ice Harbor Dam (Snake River Mile 9.7). The dams provide irrigation and flood control, important to an area with substantial farmland (grains and livestock), as well as hydroelectric power to Oregon and Washington. Locks at these two locations provide crucial transportation infrastructure for barges and other vessels transiting to the Tri-Cities and farther upriver (on the Snake River to Lewiston, ID). The McNary Pool is 50 miles long, and has a capacity of 1,350,000 acre-feet (USACE). Much of the area along the reservoir is rural with a handful of towns and unincorporated communities.

Superfund Sites & Other Historic Pollution Sites

The Hanford Site (at the upper end of the planning area on the right bank of the Columbia River) contains two Superfund Sites. One site, the (300 Area) borders the river itself while the other (200 Area) is some six miles inland. The U.S. Department of Energy, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the Washington Department of Ecology co-manage the overall cleanup of this large property under the Tri-Party Agreement (US DOE).

Socio-Economic Features

Large-Scale Restoration Sites

- There have been no large-scale restoration sites within the planning area to date.

Fishing & Sustenance

In the McNary Pool, communities may rely on natural resources for sustenance and subsistence, including salmonids. The Army Corps reports that the 10-year average collection of outgoing juvenile salmonids at the McNary Dam was 2.7 million (USACE). Also, the WDFW-managed Ringold Springs Fish Hatchery is just to the north of the planning area (along the Hanford Reach). Further, all Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission in-lieu and treaty fishing access sites are downriver of the McNary Dam (CRITFC). Waterfowl hunting within the McNary National Wildlife Refuge is very popular in the fall and winter (USFWS). Minimizing impacts to these specific resources could reduce food security impacts to these communities.

Recreation & Tourism

In addition, the Columbia River Gorge, renowned for its stunning beauty and spectacular history, supports tourism in the area, providing a wealth of recreational opportunities for fishing/boating, and agriculture (especially viticulture). Some cruise lines move up and down the Columbia and Snake Rivers as well with the Tri-Cities serving as a destination on those routes (Visit Tri-Cities).

Economic Drivers

Agriculture is a major driver of the economy in this part of the state. Use of the Columbia and the Snake Rivers as a marine transportation corridor moves a great many agricultural products out of the interior for export (Port of Benton).

Hydrology

Open to read more

The Columbia River is the fourth largest river in North America and the largest in the Pacific Northwest. It originates in Columbia Lake, high in the Canadian Rockies, where it first travels northwest, and then turns south entering the United States in Washington, where it eventually turns west and forms the border between Washington and Oregon before flowing into the Pacific Ocean. The river travels a total of 1,243 miles, providing drainage for approximately 258,000 square miles of the Western United States and British Columbia, with numerous tributaries, both rivers and creeks, adding to the flow along the way (WA ECY).

The flow of water in this portion of the river is governed by outflows from both the McNary and Ice Harbor dams. The McNary Pool has a crest elevation of 291 feet above the mean sea level. Tributaries include the Yakima and Snake Rivers. In Washington, the planning area resides within Water Resource Inventory Area Rock-Glade (WRIA 31), Walla Walla (WRIA 32), Lower Snake (WRIA 33), Esquatzel-Coulee (WRIA 36), Lower Yakima (WRIA 37), and Alkali-Squilchuck (WRIA 40). In Oregon, it includes portions of the Watermaster District 5 (headquartered in Pendleton).

Rock/Glade (WRIA 31): The Rock-Glade Watershed drains to the Columbia River and includes Rock Creek, Glade Creek, and other smaller seasonal streams. It is in south-central Washington, primarily in eastern Klickitat County and south Benton County. The climate of the Rock-Glade Watershed is primarily influenced by marine air masses traveling eastward over the Cascades and along the Columbia River. This results in more precipitation in the higher elevations (up to 24 inches in the northwest portion) that decreases from west to east (as low as 8 inches). Most of the precipitation occurs between October and April, some occurring as snow, particularly at higher elevations.

Walla Walla (WRIA 32): The Walla Walla Watershed or Water Resource Inventory Area (WRIA) 32 is defined as the area within Washington state that drains to the Walla Walla River, between the Oregon border and the river’s confluence with the Columbia. There are also small areas that drain directly to the Columbia River. It is in southeastern Washington, and includes most of Walla Walla County, and a large portion of Columbia County. The annual precipitation in the Walla Walla Watershed ranges from 8 inches per year near its confluence with Columbia River, to a little over 45 inches in the higher elevations.

Lower Snake (WRIA 33): The Lower Snake Watershed is defined as the area that drains to the lower segment of the Snake River, between its confluences with the Palouse River and the Columbia. It is in the southeastern corner of Washington State, in southern Franklin County, northern Walla Walla County, and the northwestern corner of Columbia County. The annual precipitation in the Lower Snake Watershed ranges from 8 inches per year near its confluence with Columbia River, to a little over 10 inches in the higher elevations.

Esquatzel Coulee (WRIA 36): The Esquatzel Coulee is defined as the area that drains to the coulee. It also includes several streams that drain directly to the Columbia River, many only seasonally. It is in southeastern Washington, in the northwestern portion of Franklin County, and southern areas of Grant and Adams counties. The annual precipitation in the Esquatzel Coulee Watershed ranges from 7 inches per year in the Mattawa area, to over 10 inches in the higher elevations.

Lower Yakima (WRIA 37): The Lower Yakima Watershed is defined as the area that drains to the Yakima River below its confluence with the Naches River but also includes tributaries to the Columbia River from the Hanford Reservation. It is in south-central Washington, in large portions of Yakima and Benton counties and a small northern portion of Klickitat County. Precipitation is limited in the Lower Yakima Watershed with average annual rainfall less than 20 inches per year and most of the precipitation falling between October and March.

Alkaki-Squilchuck (WRIA 40): The Alkali-Squilchuck Watershed is defined as the area that drains north and east to the Columbia River from south of Wenatchee to the city of Richland. It is in south-central Washington, in portions of Chelan, Kittitas, Yakima, and Benton counties. Much of central Washington is arid, receiving less than 20 inches of rain annually.

Climate and Winds

Open to read more

In 2024, the Pasco Tri-Cities Airport recorded a mean maximum temperature of 68°F and a minimum temperature of 41.8°F. The hottest day of the year (July 9) was 109°F and the coldest day (January 15) was 2°F. Furthermore, there were 65 days at or above 90°F and 83 days at or below 32°F. The airport also recorded 8.1 inches of rain during that year (NOAA).

Western winds carrying moisture in the air from the Pacific are pushed up against the Cascade mountains, creating a “rain shadow” (an area on the leeward side of the mountains which is sheltered from the rain). As the air rises to pass over the mountains it expands and cools, releasing moisture in the form of precipitation on the western flanks. By the time these winds pass over the Cascades there is little moisture remaining, creating the shrub steppe ecosystem that is emblematic of eastern Washington.

Tides and Currents

Open to read more

There are no tidally influenced areas within the McNary Pool. The river’s flow is governed strictly by the various dams, with the United States Army Corps of Engineers determining exactly when and how much water is allowed to pass through the spillways; there are no free-flowing waters along these portions of the Columbia and Snake Rivers.

Risk Assessment

Open to read more

The McNary Pool is plentiful in natural, cultural, and economic resources, all at risk of injury from oil spills. Potential oil spill risks include but are not limited to: oils that may sink (non-floating oils), facilities, rail transportation, oil pipelines, large commercial vessel traffic, road systems, aircraft, recreational boating, and other oil spill risks. This section briefly discusses these risks and how they could impact the GRP planning area.

Non-Floating Oils: Both refined petroleum products and crude oils are transported in bulk within this planning area. Crude oil contains a mix of hydrocarbons with a wide range of properties, while a refined product is a single type of oil, such as diesel or gasoline. Depending on the oil and the characteristics of the water the oil is spilled into, some of the oil transported in this planning area may not float.

Different oils will behave differently when spilled to water. Some heavy oils will sink immediately, some oil suspends in the water column, and lighter oils may remain on the surface and evaporate within hours. Over time, oil that initially floats can weather and mix with sediment, causing it to submerge or sink. Non-floating oils pose a specific risk to the environment because they can harm underwater or bottom-dwelling species that would otherwise be unaffected during an oil spill that remained floating on the water’s surface.

Traditional response strategies, including the booming strategies in this GRP, are designed for floating oil. However, there are steps we can take to plan for and respond to a non-floating oil spill. Non-Floating Oil Response Options and Considerations provides an overview of areas where non-floating oil might accumulate if spilled within this planning area, along with information on specific tactics that may be effective during a response. More response options recommended for finding and recovering oil below the water’s surface can be found in the Non-Floating Oil Spill Response Tool (NWACP Section 9412).

Facilities: The planning area contains three Class 1 regulated bulk petroleum facilities, all of which transfer large volumes of oil over water. Most of these large facilities are also storage terminals, housing millions of gallons of refined or crude oil in clusters of storage tanks. Several smaller facilities that fuel pleasure craft, known as Class 3 and Class 4, also operate throughout the Columbia and Snake Rivers. These regulated petroleum facilities, and the products they handle, can be viewed on the Ecology Spills Map.

Rail Transportation: Rail companies transport oil via both unit trains and manifest trains in this area. Unit trains include up to four locomotives, buffer cars, and 118 loaded tank cars transporting oil in 714-barrel (29,998 gallon) capacity USDOT-approved tank cars. Manifest trains include up to four locomotives, a mix of non-oil merchandise cars, and one or more 714-barrel (29,998 gallon) capacity USDOT-approved tank cars carrying refined oil products, such as diesel, lubrication oil, or gasoline. These trains may include emptied tank cars, each with residual quantities of up to 1,800 gallons of crude oil or petroleum products. Every train locomotive typically holds a few hundred gallons of engine lubrication oil, plus saddle tanks that each have an approximate capacity of 5,000 gallons of diesel fuel. Manifest trains may also transport biological oils and non-petroleum chemicals.

Unit trains carrying crude currently operate on specific routes. Unit trains carrying crude from the Bakken Formation in North Dakota enter Washington State near Spokane, continue along the Columbia River to Vancouver, and then head north along I-5. Like the highway systems that run along much of the Columbia River, rail transportation is present in all four Middle Columbia River GRPs.

Oil Pipelines: There is one refined petroleum pipeline in the planning area. If these pipelines were to leak or rupture, the impact on natural, cultural, and economic resources could be significant.

The Andeavor Logistics Northwest Products System is an interstate pipeline system that originates in Salt Lake City, Utah and terminates in Spokane, Washington. It crosses the Walla Walla, Snake, and Spokane Rivers in Washington. The Pasco segment is a 6-inch pipeline which carries light refined petroleum products 19 miles from the Oregon Border to Pasco, Washington. The pipeline delivers gasoline, Diesel Fuel (Ultra Low Sulfur #1 and #2), and jet fuel to two terminals run by Tesoro and Tidewater.

Large Commercial Vessel Traffic: Bulk vessels transport crude and refined oil throughout McNary Pool each carrying millions of gallons as cargo. Bulk oil is also moved by tug and barge, including crude and other potentially non-floating oils. Centerline Logistics and Tidewater are two large companies that transport fuel by water in this planning area. Additionally, the Tesoro and Tidewater Terminals (on the lower Snake River) have marine docks for tank vessels to unload and load product.

The Ports of Benton and Pasco operate marine terminals. Large commercial vessels typically carry significant amounts of heavy fuel oils and other refined products.

Road Systems: Vehicle traffic on roadways pose an oil spill risk in areas where they run adjacent to the shoreline, or cross over lakes, rivers, creeks, and ditches that drain into the Columbia, Snake, Yakima, and Walla Walla Rivers. Interstate-182, US-12, and US-395 cross these rivers. A vehicle spill onto one of these bridges or roadways can cause fuel or oil to flow from hardened surfaces into the Columbia or its tributaries. Commercial trucks can contain hundreds to thousands of gallons of fuel and oil, especially fully loaded tank trucks, and may carry almost any kind of cargo, including hazardous waste or other materials that might injure sensitive resources if spilled. Smaller vehicle accidents pose a risk as well, a risk commensurate to the volume of fuel and oil they carry.

Aircraft: The largest airport located within the planning area is the Tri-Cities Airport in Pasco. The Tri-Cities Airport (PSC) is the largest airport in the Southeastern Washington and Northeastern Oregon region and the fourth-largest air carrier airport in the state of Washington with nonstop flights to ten destination cities (Port of Pasco). A handful of smaller airfields exist in the region. The potential exists for aircraft failures during inbound or outbound flights that could result in a spill with a release of jet fuel to the McNary Pool or its tributaries.

Recreational Boating: Accidents involving recreational water craft on the McNary Pool have the potential to result in spills anywhere from a few gallons of gasoline, up to hundreds of gallons of diesel fuel. Examples of such accidents include: collisions, a vessel grounding, catching on fire, sinking, or exploding. These types of accidents, as well as problems with bilge discharges and refueling operations, the most typical types of spills to occur, have a negative impact on sensitive river resources.

Other Spill Risks: Other potential oil spill risks in the area include dam turbine mechanical failures, road run-off during rain events, on-shore or near-shore construction activities where heavy equipment is being operated, and the migration of spilled oil through soil on lands adjacent to the river or along creek or stream banks. Also, the Energy Northwest Columbia Generating Station (located on the Hanford Site) could be the origin point of a spill to water via the facility’s outfalls.

Resources at Risk

Open to read more

This section provides a summary of natural, cultural, and economic resources at risk in the planning area, including those resources at risk from oils with the potential to sink or submerge. It provides general information on habitat, fish, and wildlife resources, and locations in the area where sensitive natural resource concerns have been identified. It offers a summary of cultural resources that include fundamental procedures for the discovery of cultural artifacts and human skeletal remains. General information about flight restrictions, wildlife deterrence, and oiled wildlife can be found near the end of this section. A list of economic resources in the area is downloadable from the table of contents on this webpage.

This section is purposely broad in scope and should not be considered comprehensive. Some of the sensitive resources described in this section cannot be addressed in Response Strategies and Priorities because it is not possible to conduct effective response activities in these locations. Additional information from private organizations or federal, state, tribal, and local government agencies should also be sought during spills. This material is presented with enough detail to give general information about the area during the first phase of a spill response. During an actual incident, more information about resources at risk will be available from the Environmental Unit in the Planning Section.

Note: specific resource concerns related to areas that already have designated protection strategies may be found in the “Resources At Risk” column of the matrix describing the individual strategies.

The information provided in this section can be used in:

- Assisting the Environmental Unit (EU) and Operations in developing ad hoc response strategies.

- Providing resource-at-risk “context” to responders, clean-up workers, and others during the initial phase of a spill response in the GRP area.

- Briefing responders and incident command staff that may be unfamiliar with sensitive resource concerns in the GRP area.

- Providing background information for personnel involved in media presentations and public outreach during a spill incident.

- Providing information on benthic and water column species or cultural resources present to assist in planning for oils with the potential to sink or submerge.

Natural Resources at Risk – Summary

Open to read more

This area is composed of a wide variety of aquatic, riparian, and upland habitats. These varied habitats support a complex diversity of wildlife species, including large and small mammals, songbirds, birds of prey, upland birds, and waterfowl, as well as numerous reptiles and amphibians. Some species are resident throughout the year, while others seasonally migrate through the sub-basin.

This area contains a wide variety of aquatic, riparian, and upland habitats. These habitats support many of Washington’s salmonid species as well as a complex diversity of other wildlife. In addition to those species directly at risk to oil spills, others (due to their life histories and/or behaviors) are unlikely to become directly oiled during a spill incident but may be disturbed by response operations such as cleanup and reconnaissance. Some of the bird species are resident throughout the year, but many others seasonally migrate through the area.

Several of the species found in this area have been classified under the Federal Endangered Species Act or by the Washington State Fish and Wildlife Commission.

Classification types are listed below:

- Federal Endangered (FE)

- Federal Threatened (FT)

- Federal Candidate (FC)

- State Endangered (SE)

- State Threatened (ST)

- State Sensitive (SS)

Federal and State Threatened, Endangered, and Sensitive species that may occur within this area, at some time of the year, include:

Mammals:

- Washington ground squirrel [SE (OR)]

Birds:

- American white pelican [SS (WA)]

- common loon [SS (WA)]

- greater sage grouse [FC/ST (WA)]

- ferruginous hawk [ST (WA)]

- sandhill crane [SE (WA)]

- yellow-billed cuckoo [FT/SE]

Fish:

- bull trout [FT]

- chinook salmon, Fall (Snake River) [FT/ST (OR)]; Spring/Summer (Snake River) [FT/ST (OR)]; Spring (upper Columbia) [FE]

- chum salmon (Columbia River) [FT]

- sockeye salmon (Snake River) [FE]

- steelhead trout (middle Columbia) [FT]; (Snake River) [FT]; (upper Columbia) [FT]

- shellfish: western ridged mussel [FC]

Amphibians:

- Northern leopard frog [SE]

Insects:

- monarch butterfly [FC]

Critical habitats:

These are the specific areas occupied by an endangered or threatened species that contain the physical or biological features that are essential to the conservation of that species – and that may need special management or protection. Critical habitat may also include areas that were not occupied by the species at the time of listing but are essential to its conservation.

- bull trout has designated critical habitat areas within the McNary GRP zone.

General Resource Concerns

Open to read more

Habitats:

- Wetlands in this region are all freshwater and range from seasonal open marshes to forested swamps along rivers and streams. All wetland types support a diverse array of amphibian, bird, insect and fish and wildlife species.

- Side channels and impounded areas provide feeding and resting areas for waterfowl and herons and are important rearing areas for juvenile fish.

- Several rivers and smaller tributary streams flow into the mainstem of the Columbia River within this area. These act as important salmon migration routes and spawning areas, as well as providing rearing habitat for juvenile salmonids and resident fish species. Stream mouths are concentration areas for anadromous fish and are feeding areas for a variety of birds. Wintering waterfowl use the mainstem Columbia as well as these rivers as some of the open water associated with the lower reaches of the rivers and streams.

- Riparian areas serve as transitional zones between the uplands and the rivers and consequently are heavily used by a variety of wildlife. They contribute to nearshore fish habitat by providing shade, cover, and food. They also play a crucial role in supporting a large diversity and abundance of songbird species as breeding, migrating, and overwintering habitat.

- Islands provide important nesting areas for a variety of bird species, as well as habitat for a variety of mammals.

- Numerous habitat restoration sites exist along the middle Columbia River and its tributaries. Often, significant resources have been invested in these locations to improve stream conditions specific to salmon recovery.

- Subsurface Habitats The shallow subsurface habitats that occur within this region include:

- Fine sediments (mud/silt/sand) – Associated with slow/still water flows. May have aquatic vegetation present.

- Animals associated with these areas may be: salmonid and resident fishes; birds (dabbling and diving ducks); semi-aquatic mammals (muskrat, beaver, etc.); shellfish (freshwater clams); amphibians and reptiles (frogs, newts, salamanders, turtles, etc.); insects caddis flies, mayflies, dragonflies, and stoneflies). Many other animals also utilize these areas for foraging.

- Coarse sediments (gravel/cobble) – Associated with moderate water flow. May have aquatic vegetation present.

- Animals associated with these areas may be salmonid and resident fishes; birds (dippers, harlequin ducks); semi-aquatic mammals (muskrat, beaver, etc.); shellfish (pearlshell mussels, crayfish); amphibians and reptiles (tailed frogs, torrent salamanders; insects caddis flies, stoneflies). Many other animals also utilize these areas for foraging.

- Bedrock – Associated with fast water with little or no deposition of loose bed materials. Aquatic vegetation not typically present.

- Animals associated with these areas tend to be mostly cold-water (salmonid) fishes, birds (dippers, harlequin ducks), and amphibians (torrent salamanders).

- Fine sediments (mud/silt/sand) – Associated with slow/still water flows. May have aquatic vegetation present.

Fish:

- Various salmonids (both juvenile and adults) are present in the river above the John Day Dam throughout the year. Millions of juvenile salmonids move downstream through this area and use this area for rearing and foraging as they prepare for migration to the ocean. Returning adult salmonids of various types and stocks support significant tribal and recreational fisheries.

- Anadromous fish (other than salmon) in this region include American shad and Pacific lamprey.

- Resident fish present year-round in the river include white sturgeon, walleye, largemouth bass, crappie, perch, bullheads, and northern pike minnow.

Wildlife:

- Significant waterfowl concentrations exist throughout this GRP region from fall through spring. Hundreds of thousands of geese, swans and dabbling ducks may occupy this region during peak periods. Resident and migratory waterfowl heavily utilize the islands, backwaters, wetlands and adjacent uplands of the region from fall through spring. Numerous islands in this sub-region also provide nesting habitat for resident waterfowl.

- Bald eagles and great blue herons are nesting residents and may be found year-round throughout the region. Peregrine falcons are commonly found as winter and spring visitors. Other raptors, including burrowing owl, golden eagles, northern harrier, osprey, and prairie falcon are also found in this area.

- Resident and migratory songbirds heavily utilize riparian habitats year-round and are susceptible to response activities that disturb riparian vegetation.

- Mammals common to the region include managed species such as mule and whitetail deer, etc. Other mammals present include semi-aquatic species such as beaver, muskrat, river otter, mink and raccoon. Because of their habitat preferences, these latter species are vulnerable to contact with spilled oil.

- Amphibians and reptiles are found throughout this area.

Specific Geographic Areas of Concern – Overview

Open to read more

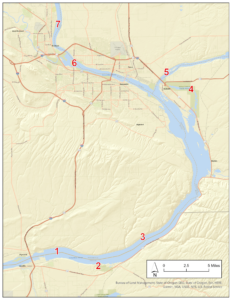

In general, areas of concern include shorelines with natural riparian vegetation, islands, wetlands, stream mouths, and shallow backwater areas – especially those adjacent to natural shorelines. Specific areas of concern are listed below. The item number in the list corresponds to the numbered location on the following map.

- McNary Pool (~RM 292-296): Large waterfowl concentration area. Raptor nesting (including osprey, prairie falcon, and ferruginous hawk) in area. Salmonids and resident fish.

- Hat Rock and vicinity (~RM 298-301): Shallow water habitat, waterfowl, shorebird nesting and wintering areas. Salmonids and resident fish. Public recreation area (Hat Rock State Park).

- Van Skinner Island and vicinity (~RM 302-305): Waterfowl concentration area. Raptor nesting (including golden eagle, prairie falcon, and ferruginous hawk) in area. Salmonids and resident fish.

- McNary National Wildlife Refuge (~RM 314-325):Islands, sloughs, and wetlands provide critical resting and feeding areas for wildlife and serve as important rearing areas for resident fish and juvenile salmonids. The benthic habitats in streams and rivers may include freshwater mussels and immature lamprey. This area is a major artery of the Pacific Flyway used by migratory waterfowl, shorebirds, wading birds, and raptors, primarily in October through February. Riparian habitats are heavily used by wildlife including river otter, beaver, and mink raccoon. Shrub-steppe habitat is utilized by many terrestrial species.

- Strawberry Island and vicinity (~RM 3 on Snake River): Strawberry Island is part of McNary National Wildlife. Riparian and wetland habitats. Migratory waterfowl concentration and nesting areas (including American white pelican [SE]). Great blue heron foraging area. Salmonid and resident fish present year-round.

- Bateman Island and vicinity (~RM 333-337) and lower Yakima River: Waterfowl and shorebird migration and wintering concentration area. Concentration and breeding areas for Western grebes [SC], and Common loons [SS] on main stem. Yakima River delta serves as a biodiversity corridor, consisting of mixed riparian, wetland, and shrub-steppe used by a variety of species. Salmonid habitat (including Bull trout [FT/SC]).

- Hanford Reach islands (~RM 339-343). Waterfowl and shorebird migration, wintering, and nesting concentration area. Concentration area for American white pelican [SE]. Breeding area for Long-billed curlew. Great blue heron and Forster’s tern nesting colonies.

Cultural Resources at Risk – Summary

Open to read more

Culturally significant resources are present within the planning area. Information regarding the type and location of cultural resources is maintained by the Washington Department of Archeology and Historic Preservation (WDAHP). This sensitive information is made available to the Washington Department of Ecology for oil spill preparedness and response planning. The Tribal Historic Preservation Offices (THPOs) or Cultural Resource Departments of local tribes (see table below) may also be able to provide information on cultural resources at risk in the area and should be contacted, along with WDAHP, through normal trustee notification processes when significant oil spills, or smaller spills above reportable thresholds, occur in the area.

During a spill response, after the Unified Command is established, information related to specific archeological concerns will be coordinated through the Environmental Unit. To ensure that tactical response strategies do not inadvertently harm culturally sensitive sites, WDAHP should be consulted before disturbing any soil or sediment during a response action, including submerged soils or sediments. WDAHP and/or the Tribal governments may assign a person or provide a list of professional archeologists that can be contracted, to monitor response activities and cleanup operations for the protection of cultural resources at risk. Due to the sensitive nature of such information, details regarding the location and type of cultural resources present are not included in this document. However, some sites are well known due to their listing on National or State Registers and some larger areas have been designated Archaeological Districts. See the Site Description section of this plan for further information.

MCRM-GRP Cultural Resource Contacts

| Contact | Phone | |

| Washington Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation | (360) 586-3065 | Rob.Whitlam@dahp.wa.gov |

| Oregon Heritage State Historic Preservation Office | (503) 986-0690 | oregon.heritage@oregon.gov |

| Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, THPO | (509) 307-2009 | Rose_Ferri@yakama.com |

| McNary National Wildlife Refuge | (509) 440-0552 | salvatore_caporale@fws.gov |

| Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, THPO | (541) 429-7234 | CareyMiller@ctuir.org |

| Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde, THPO | (503) 879-2084 | thpo@grandronde.org |

| Nez Perce Tribe, THPO | (208) 843-2253 | keithb@nezperce.org |

| Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, THPO | (541) 553-2002 | lawrence.squiemphen@ctwsbnr.org |

Discovery of Human Skeletal Remains

The finding of human skeletal remains will be reported to the county medical examiner/coroner and local law enforcement in the most expeditious manner possible. The remains will not be touched, moved, or further disturbed. The county medical examiner/coroner will assume jurisdiction over the human skeletal remains and make a determination of whether those remains are forensic or non-forensic. If the county medical examiner/coroner determines the remains are non-forensic, then they will report that finding to the Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation (DAHP) who will then take jurisdiction over the remains. The DAHP will notify any appropriate cemeteries and all affected tribes of the find. The State Physical Anthropologist will make a determination of whether the remains are Indian or Non-Indian and report that finding to any appropriate cemeteries and the affected tribes. The DAHP will then handle all consultation with the affected parties as to the future preservation, excavation, and disposition of the remains.

Any human remains, burial sites, or burial-related materials that are discovered during a spill response must be treated with respect at all times (photographing human remains is prohibited to all except the appropriate authorities). Refer to National Historic Preservation Act Compliance Guidelines (NWACP Section 9403) during an emergency response.

Procedures for the Discovery of Cultural Resources

If any person monitoring work activities or involved in spill response believes that they have encountered cultural resources, all workers must stop immediately and notify the Unified Command and Cultural Resource Specialist. The area of work stoppage must be adequate to provide for the security, protection, and integrity of the material or artifact(s) discovered.

Prehistoric Cultural Resources (May include, but are not limited to, any of the following items):

- Lithic debitage (stone chips and other tool-making byproducts)

- Flaked or ground stone tools

- Exotic rock, minerals, or quarries

- Concentrations of organically stained sediments, charcoal, or ash

- Fire-modified rock

- Rock alignments or rock structures

- Bone (burned, modified, or in association with other bone, artifacts, or features)

- Shell or shell fragments

- Petroglyphs and pictographs

- Fish weirs, fish traps, and prehistoric water craft

- Culturally modified trees

- Physical locations or features (traditional cultural properties)

- Submerged villages sites or artifacts

Historic cultural material (May include any of the following items over 50 years old):

- Bottles, or other glass

- Cans

- Ceramics

- Milled wood, brick, concrete, metal, or other building material

- Trash dumps

- Homesteads, building remains

- Logging, mining, or railroad features

- Piers, wharves, docks, bridges, dams, or shipwrecks

- Shipwrecks or other submerged historical objects

Economic Resources at Risk – Summary

Open to read more

Socio-economic sensitive resources are facilities or locations that rely on a body of water to be economically viable. Because of their location, they could be severely impacted if an oil spill were to occur. Economically sensitive resources are separated into three categories: critical infrastructure, water dependent commercial areas, and water dependent recreation areas. The appendix provides a list of economic resources for this planning area.

General Information

Open to read more

Flight restriction zones

The Environmental Unit (Planning Section) may recommend flight restriction zones to minimize disturbance or injury to wildlife during an oil spill. Pilots/operators can decrease the risk of aircraft/bird collisions, prevent the accidental driving of wildlife into oiled areas, and minimize abandonment of nests by keeping a safe distance and altitude from these identified sensitive areas.

The Air Operations Branch (Operations Section) will manage all aircraft operations related to a response and will coordinate the establishment of any Flight Restriction Zones as appropriate. Environmental Unit staff will work with the Air Operations Branch Director to resolve any conflicts that arise between flight activities and sensitive resources.

In addition to restrictions associated with wildlife, Tribal authorities may also request notification when overflights are likely to affect culturally sensitive areas within reservations. See Oil Spill Best Management Practices (NWACP Section 9301) for more information on the use of aircraft and helicopters in open water and shoreline responses.

Wildlife Deterrence

The Wildlife Deterrence Unit within the Wildlife Branch (Operations Section) manages wildlife deterrence operations. These are actions intended to minimize injuries to wildlife by keeping animals away from the oil and cleanup operations. Deterrence activities may include using acoustic or visual deterrent devices, boats, aircraft or other tools. The Wildlife Branch works with state and federal agencies, and the Environmental Unit (Planning Section), to develop deterrence plans as appropriate.

For more information see the Northwest Wildlife Response Plan (NWACP Section 9310) and Northwest Area Wildlife Deterrence Resources (NWACP Section 9311).

Oiled Wildlife

Capturing oiled wildlife may be hazardous to both personnel and the affected animals. Incident personnel should not try to approach or capture oiled wildlife but should report any observations of oiled wildlife to the Wildlife Branch (Operations Section).

For more information see the Northwest Wildlife Response Plan (NWACP Section 9310).

Wildlife Refuges and Wilderness Areas

McNary National Wildlife Refuge is located within this region.

Aquatic Invasive Species

The waters of this region may contain aquatic invasive species (AIS) – species of plants and/or animals that are not native to an area and that can be harmful to an area’s ecosystem. If so, preventative actions may be required to prevent the spread of these species as a result of spill response activities and the Environmental Unit is able to recommend operational techniques and strategies to assist with this issue.